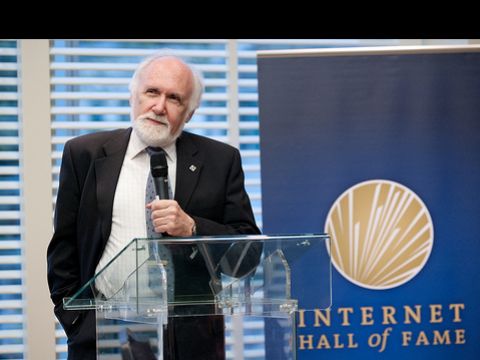

In April, Klensin was inducted into the Internet Society’s (ISOC) Internet Hall of Fame, entering alongside such notable names as Vint Cerf, Bob Kahn, and Larry Roberts. But unlike many of the other inductees, Klensin isn’t known for one seminal idea or creation you can describe in a sentence or two. If you look back over his role in the evolution of the Internet, he’s more like the jack of all trades.

Klensin was part of a small group of academics and other minds who built the ARPAnet — a research network funded by the U.S. Department of Defense — and gradually turned it into the worldwide internet we know today. He’s the author of over 40 Request for Comments, or RFC, the technical documents that have defined the architecture of the network for more than 40 years.

The way Klensin tells it, he grew up in southern Arizona, enrolled as student at MIT, and “never quite escaped.” His area of study was political science, but part of his work involved how communications could influence social and policy sciences, and that’s how he wound up on the ARPAnet. At MIT, he worked for and alongside J.C.R. Licklider, who planted many of the seeds that led to the ARPAnet, and as this research network was getting started in the late ’60s, Klensin had a front-row seat.

“The projects I was working on — or leading — starting at the end of the 1960s became heavy users of the ARPAnet,” he says. “The research environment was open enough, and open enough to input, that our comments and design suggestions were welcomed and incorporated in the network — or not — on the same basis that internal suggestions would have been.”

In this way, he was involved in the development of various ARPAnet protocols, including the file transfer protocol, or FTP, a means of moving files between machines, and and the Simple Mail Transfer Protocol, or SMTP, a standard for sending electronic mail.

Klensin also worked alongside a researcher named Jon Postel, who was one of the key players in the design of the ARPAnet and later created the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority, or IANA, which oversaw the network’s protocols and naming system. IANA’s duties would later pass to ICANN, the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers, and Klensin was one of the many who helped bridge the gap between the two after Postel’s death.

He worked particularly hard to establish communication between the ARPAnet and other early networking efforts and to help bring networking to developing countries.

But if you ask him what he’s most proud of — or what work best represents his contribution to internet history — Klensin demurs. “I have no idea how to answer a question like that,” he says. “I stayed involved. I advised. I brought multiple perspectives to the work. I tried to understand all the systems involved rather than focusing on a particular piece of the puzzle and treating one or two pieces in isolation and hoping everything else would work out.”

That said, he does point to his work “internationalizing” the Internet’s naming systems. But he’s careful to point of that this was a very much a team effort. Of course, you can say the same about the development of the Internet as a whole. In some ways, John Klensin is a nice metaphor for the evolution of this worldwide network. It was created over so many years, with so many small steps forward.