But he takes even more pride in what he calls his “army” of students, who are now doing cutting-edge research worldwide and teaching a new generation of students themselves. He remains in close contact with many of them; in fact, when we caught up to him in late May, he was preparing for a visit from a former student who lives and works in China. He says of teaching and mentoring: “It’s the most pleasurable part of my job. You see that you have inspired people to do the best work they can, and investigate areas you may not even have thought of, and you watch them take off and fly. I have enjoyed this aspect of my career so much that I never even look at it as a job.”

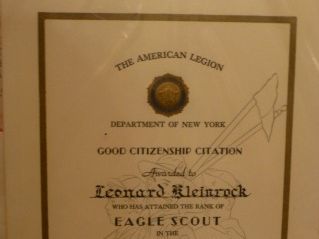

Still, among all his awards, it’s one for his learning, not his teaching, that has a special place of honor in his California home. A montage of prized possessions, including honorary doctorates, fills a frame, but the one front and center – the only one not overlapped by any other – is his Eagle Scout award. Why is that so important to the man who coordinated the transmission of the first message to pass over the Internet? Well, because it set him on his lifetime course with confidence and optimism.

“It was the first project I ever undertook that I thought was just beyond my reach. But I kept at it and succeeded. That was a life lesson for me,” he says. “It proved to me that if you think something’s beyond your grasp, you should go for it anyway – and that if you work hard and keep at it, you will reach it.”

He likes to remind college students that they’re benefiting from 4,000 years of wisdom. “Here are Maxwell’s equations, here are the great works of art and literature – they’re all handed to you when you’re in school,” he says. “But when it’s your turn to create something of your own, it’s a lot of work. You hit a wall. At that point, it’s good to remember that everyone hits that same wall; it’s the great ones who continue chipping away until they get through it, to advance human knowledge and culture. But you have to believe you can do it.”

There’s a bit more advice Dr. Kleinrock would give students today: “Be adaptable. When a field gets so crowded that you can’t even keep up with the literature, it’s time to shift fields. Be willing to explore new areas that may turn out to be more exciting than what you’d been devoting your time to.”

He sees interdisciplinary work – combining computer science with bio-engineering and the natural sciences — as being among the most exciting fields these days. “Nature has a tremendous amount to teach engineering,” he says. “To combine the natural sciences with computer science could have tremendous impact.”

And, in full graduation mode (he was set to give a commencement address at Concordia University in Quebec in June), the man with 21 merit badges left us with a final thought worth absorbing: “Never be afraid of failure. For any progress to be made, failure is necessary.”