In Metcalfe’s building there in Palo Alto, scientists were busily carrying out their own individual activities, but they clearly needed to be connected to one another, and to the great research universities. The ARPANET, the predecessor of the Internet, was in its infancy, and the trick was going to be to extend it into the building. (“Also,” he notes, “to enable us all to print on our new 500-dpi, page-per-second laser printer.”)

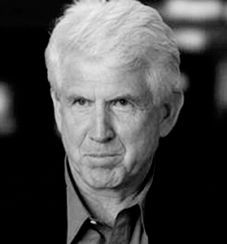

To 26-year-old Metcalfe, a newly-minted PhD in computer networking, making that connection was the challenge of a lifetime. He relished what he calls his “good fortune to be the first person in the world to be given the problem of connecting a roomful of computers.”

Metcalfe’s wildly successful response to that challenge was nothing less than the co-invention, with colleague David Boggs, of Ethernet – the technology for creating what eventually would come to be called local area networks (LANs) using coaxial cable.

Today, Ethernet connections are so familiar that it seems as if the technology has always been there. Only it hasn’t. PARC scientists could send out electronic packets of information, but they couldn’t get information back because, on their journey through the building, the packets regularly would collide with other packets moving along the same cable, and be knocked “off-course.” Metcalfe’s task, essentially, was to program those collisions out of existence.

Part of the genius of Metcalfe’s Ethernet invention was a distributed algorithm for taking turns millisecond by millisecond, using the cable (the “ether”) to carry PARC’s millisecond-long data packets at 2.94 million bps. He derived the algorithm from the University of Hawaii’s ALOHAnet, which used randomized retransmissions to take turns. As the number of collisions increased, Ethernet stations (Altos at first) would back off, to keep the throughput of the channel near optimal.

“I specified that at each collision, we’d double the mean of the time we’d wait to resend,” Metcalfe says. Each station’s random number would need to be a multiple of 50 microseconds.

It’s amazing now to recall that the speeds at which information traveled in the 1970s were orders of magnitude slower than today’s speeds. For example, on the day (May 22, 1973) he circulated his memo containing a rough schematic of how Ethernet eventually would work (that’s the day he credits as Ethernet’s invention), Metcalfe says, “I had bandwidth coming to my desk at 300 bps. By contrast, that first 2.94-million bps Ethernet connection was about 10,000 times faster.”

For his work in creating Ethernet, thus speeding up the communications and lives of millions of people worldwide, Metcalfe was inducted into the Internet Hall of Fame in August 2013. But the first sure indication of the importance of Ethernet came 40 years earlier. Shortly after he’d networked the PARC work stations, someone, for some unknown reason, found the little metal tip at the end of the coaxial cable they were all sharing – and removed it. Twenty or so computer scientists simultaneously stood up in their cubicles and looked around, saying, “Oh, no! The network’s down!”

That’s when it became clear that Ethernet was no longer an option … it was a necessity.