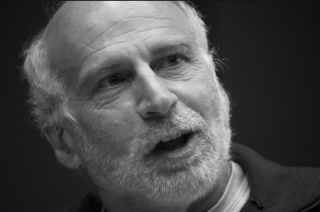

“I wound up having two great rides,” Klingenstein says of his career. His initial work involved leading the growth of the Internet in the Western United States. As he undertook that work and evangelized its significance to others, the importance of Internet privacy and security became a compelling point that refocused the second half of his work’s trajectory. In both areas, Klingenstein concentrated on what he saw as the projects most likely to make a beneficial impact. “If you want to connect the dots,” he says, “the theme was making a difference.”

In the late 1970s, the young man who’d grown up in New Jersey from a background he declares unremarkable (“Jersey was a very uninspiring place at that time.”), completed his PhD in mathematics at the University of California, Berkeley. In 1985, Klingenstein took an academic position at the University of Colorado. But his teaching career didn’t exactly blossom. “I didn’t do particularly well as a researcher or a faculty member,” he says. “I was treading water until I switched over to the management side.”

At first, Klingenstein managed the computer center at the University of Colorado in Colorado Springs. This was in the early days of TCP/IP, the standard protocol allowing computers to connect over long distances. Teaching an early networking class gave him the technical background and insights into the potential of networks that most people involved in computing still didn’t have at that time.

“But all that stuff didn’t really stir me,” he says. Until, that is, he began to show the technology to people who were less technically inclined than he. He recalls demonstrating the power of an academic network to his boss, a psychology professor. “We’re not really connected to a place in Germany,” she said. Said Klingenstein, “Yes, we really are.”

During the nearly decade and a half that Klingenstein helped deploy Internet services throughout the West, he worked closely with the National Science Foundation (NSF). He participated in the initial NSF meetings focused on launching NSFNET, the network that connected research and educational institutions across the United States. He also held leadership positions in Westnet, the original NSF network serving Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming, helping ensure largely rural regions were not left behind in Internet development. Klingenstein also led through the NSF-funded clearinghouse that tracked the Internet’s information infrastructure, the Federation of American Research Networks (FARnet).

In the technologically advanced town of Boulder, Klingenstein saw an opportunity to bring the area’s K-12 school district online with the first NSF grant ever awarded to wire a school district. Having established that, he sought a similar grant from the National Telecommunications and Information Administration to create the Boulder Community Network, the second www-based community network site in the world.

Of his participation in the work of bringing the West online, Klingenstein modestly says, “I was one of 500 who were ‘in the room.’” But of his work around privacy on the Internet he says, “I was one of more like ten people.”

His interest in privacy dated back to that earlier moment when he connected his boss’s computer to a computer in Germany. As a psychology professor, she was more interested in people than technology. But as she and Klingenstein sat in her office one snowy Colorado afternoon, they moved from a Germany-based site to a Cornell University site that provided anonymous support to students experiencing emotional distress. Called Uncle Ezra, the site allowed students access to informal advice and counseling, provided by an anonymous school therapist. Posted to Uncle Ezra at this particular moment was a note from a student in deep distress; specifically, it detailed their intention to commit suicide. The therapist behind Uncle Ezra had replied with earnestness, comfort, and advice, altering the desperate student’s plans. And it had all been anonymous.

That encounter demonstrated the value of the burgeoning Internet to Klingenstein’s humanist boss, and, to both of them, the value of the network’s privacy and anonymity. Few people would share a suicide note if they had to give identity, Klingenstein realized. “It was a transformational moment,” he recalls.

From that snowy day in 1985, even though Klingenstein continued for several years to work with pure technology and the policies that would manage the Internet, “The idea that we could do all this while preserving privacy was foremost in my mind,” he says.

In the late 1990s, Klingenstein turned his focus full force to envisioning and developing the Internet’s trust and identity layers. Klingenstein approached the problem with the belief that if Internet users surrendered privacy, “… you’d never get it back.” He was looking for a way to authenticate locally but act globally. The solution proved to be privacy preserving by allowing characteristics other than identity to facilitate access–for example that a user was a student but not which exact student.

Serving as the director of the Internet2 Middleware and Security Initiative, Klingenstein led the development and dissemination of middleware interoperability and set best practices in place. “We got involved with the federal government early on in their efforts to create Internet identity,” he says. The government’s philosophy was to build a “‘we-really-know-who-you-are’” system, says Klingenstein. His intention was to develop technology that could create identity, “But we’re going to begin with an anonymous approach.”

It was complicated work. “There was no real advocacy against privacy,” he says of convincing others of privacy’s importance. “But there was advocacy against the complexity that preserving it led to.”

As he dove deeper into trust and identity issues, Klingenstein and colleague Bob Morgan founded the Shibboleth Identity Management System, which became an internationally adopted standard for preserving identity. The Shibboleth name drew from an Old Testament reference tied to the correct pronunciation of a term that could be said a certain way by tribespeople and used to determine who could safely enter the community without additional credentials or identification. Klingenstein notes that the original use of the word Shibboleth was perhaps the first known biometric authentication system.

“We picked the word Shibboleth specifically to capture the fact that this was a privacy-preserving set of technologies that could carry characteristics about who you were without personally identifying you,” he says. Other internationally adopted standards Klingenstein helped launch included the InCommon Federation, which provides secure, single sign-on access to cloud and local services; and the eduPerson object-class standard to facilitate communication between institutes of higher learning.

In working on the trust and identity layer of the Internet, Klingenstein found it extremely useful to follow the design principles of the original network layer, such as modularity, a layered approach and even rules of being cautious in sending parameters and generous in receiving them. “In some sense,” he says, “the design principles of the Internet are as valuable as the technologies they have created.”

Indeed, the technology that maintains privacy on the Internet today is largely shaped by Klingenstein’s work. Usually humble and one to generously share credit, he admits to being, “consequential in privacy-preserving.” Where did the drive for that world-changing work come from? “I was a young’un when John Kennedy was killed,” he remarks. “And for everyone who was young at that time, that was a turning point. At that moment, you began to think, ‘How do I contribute back?’”