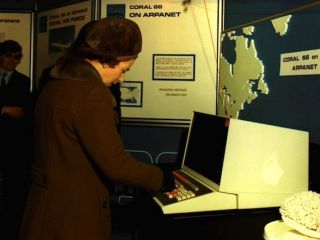

That’s Her Majesty in the photo, and if the year isn’t immediately obvious from the computer terminal she’s typing on — or from her attire — you can find it on the wall, just to her left, printed on one of the signs trumpeting the arrival of the ARPAnet.

The date was March 26, 1976, and the ARPAnet — the computer network that eventually morphed into the internet — had just come to the Royal Signals and Radar Establishment, a telecommunications research center in Malvern, England. The Queen was on hand to christen the connection, and in the process, she became one of the first heads of state to send an e-mail.

It was Peter Kirstein who set up her mail account, choosing the username “HME2.” That’s Her Majesty, Elizabeth II. “All she had to do was press a couple of buttons,” he remembers, “and her message was sent.”

Kirstein’s role in the first royal e-mail was only appropriate. He’s also the man who first brought the ARPAnet to Great Britain, setting up a network node at the University of London in 1973. Throughout the ’70s and on into the ’80s, he would oversee Britain’s presence on ARPAnet and help push this sprawling research network onto the all-important TCP/IP protocols that gave rise to the worldwide internet as we know it today.

This past April, in recognition of his dogged pursuit of internetworking in Great Britain — if not his deft choice of royal usernames — Kirstein was inducted into the Internet Society’s (ISOC) Internet Hall of Fame. Part of the hall’s inaugural class, he was joined by such names as Vint Cerf, Bob Kahn and Tim Berners-Lee.

Kirstein grew up in Britain. He studied mathematics and engineering at Cambridge and the University of London. And completing his PhD, he was a researcher with General Electric in Zurich, Switzerland. But over the years, he also spent quite a bit of time at Stanford University and the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) in the States.

In the 60s, at UCLA, he met Vint Cerf — who would one day help create the TCP/IP protocols — and as the 70s rolled around and he settled into professorship at the University of London, he had developed relationships with various other researchers who had recently spread the ARPAnet across various U.S. research operations, including Larry Roberts, the man who originally designed the thing for the U.S. Department of Defense.

When Roberts decided that the ARPAnet should stretch from the U.S. to Norway and Britain via an existing trans-Atlantic telecommunications link, Kirstein was chosen to facilitate the British connection. The original idea was to connect the ARPAnet to the network built by Britain’s National Physical Laboratory and Donald Davies — who coined the term network packet and played a role in the early design of the ARPAnet — but according to Kirstein, a link to the NPL was ruled out because of political reasons. The UK was working to get into the European Economic Community, and apparently, Europe would frown on that sort of direct cooperation between the NPL and the U.S. Defense Department. So the task fell to Kirstein instead.

With a year’s worth of funding from the British Post Office for the link between Norway and Britain (the trans-Atlantic connection went to Norway first) and an additional 5,000 pounds from Davies and the NPL, Kirsten set up his ARPAnet node at the University of London.

He would take the network to other parts of Great Britain — including the Royal Signals and Radar Establishment — but he also helped hook the ARPAnet into SATNET, a satellite network that could connect various other European countries. Kirstein was on the other end of the line in November 1977, when researchers riding across Northern California in a bread truck first used TCP/IP to send data across three separate networks: a packet radio wireless network, the ARPAnet, and SATNET. The message bounced from San Francisco to Norway and Britain and back again in an demonstration of what Vint Cerf calls “true inter-networking.”

By 1983, TCP/IP was officially rolled out across the ARPAnet, and as other networks adopted the protocols in the coming years, the internet was born.

It was revolution in digital communication. But to the Queen, it was old hat. She could even say that the first message she sent across the ARPAnet in 1976 wasn’t without some real hacker cred. The Royal Signals and Radar Establishment has developed a programming language called Coral 66 — it’s also mentioned on the wall, just to her left — and this was the subject of her missive.

“This message to all ARPAnet users announces the availability on ARPAnet of the Coral 66 compiler provided by the GEC 4080 computer at the Royal Signals and Radar Establishment, Malvern, England,” the message read. “Coral 66 is the standard real-time high level language adopted by the Ministry of Defence.”