When you listen to Klaas Wierenga talk about the development of eduroam, the access tool that provides academics and researchers with wifi roaming services at campuses around the world, you hear one phrase over and over again: “So I said, ‘Sure!’”

That spirit of affirmation is what made the development of eduroam possible. Saying “yes” to working together is what the system is all about. In fact, Wierenga calls eduroam “the poster child for collaboration.”

Launched in 2002, eduroam is currently available in 106 territories around the globe, connecting hundreds of academic institutions. Travelling students, faculty, and staff log in via their home-institution network no matter what campus they happen to be on. End-to-end encryption means that private-user credentials are only available to the home institution.

In addition to giving visitors wifi access, eduroam relieves the host institution from having to provide guest access. eduroam can also be used as an institution’s complete wireless network to serve its own campus.

The man who planted the eduroam seed that “grew into a very big flower,” as Wierenga puts it, was an indifferent high school student. “I would pass every year with the absolute minimum,” he says. The university environment, though, sparked his interest. Wierenga performed his government-mandated civil service by volunteering at the university computer lab. The project he worked on was coordinated with SURFnet, the Netherlands’ National Research and Education Network (NREN). After a year and a half, the organization hired him full time.

At SURFnet in the early 2000s, says Wierenga, “A few of us would spend days sitting with our feet on a chair, just talking about things and bouncing ideas off each other.” They weren’t idle, though. His team had just deployed the fastest-to-date student housing network and were developing a technology to separate Internet traffic in different buildings. Team members also knew personally the challenges of campus computing. “The fact that we were so integrated into the academic community helped us come up with ideas that served them.” In particular was the problem that arose when traveling. “Whenever you were a student or an employee of a university and you visited another university, it was a pain to gain access to the Internet.”

But a Netherlands technical university approached the group with a different problem: individual faculties had deployed their own wifi networks, so students in other buildings could not get access across departments. Could SURFnet help? “So I said, ‘Sure,’” says Wierenga. But remembering his own experiences with the pain of access, he took the solution to the next level.

“I had an idea to combine two technologies that we already were deploying, the one to separate student traffic and another to provide a dial-up network. Essentially the combination of the two allowed for guest access to wifi networks.”

With the new system launched in the Netherlands, other universities started paying attention. “The UK was on board, then we had a conference in Croatia and the local research and education network approached me and said, ‘Do you think we could set up a demo,’ so I said, ‘Sure.’” After a successful pilot, GÉANT, the pan-European research and education network, adopted the technology as a service for all its members…and eduroam was born.

When Portugal and Spain began to use eduroam, the next natural step was for Latin America to pick up the technology. U.S. campuses were further behind. Wierenga points out that travel between U.S. institutions is less common, unlike in Europe, where cities and campuses are close together, and traveling is easy and commonplace.

Wierenga generously credits others in the development and spread of eduroam. “Yes, it was my idea, but, for example, I got an intern, Paul Dekkers, who turned out to be really good. He asked if I had any graduate work so I said, ‘Sure.’ Now he’s one of the big guys, in the technical sense, in the eduroam community.”

Some of those others helped build the features that make eduroam the robust and durable tool it has become. After about eight years at SURFnet, Wierenga left to become a senior consulting engineer and identity architect at Cisco Systems as part of the Research and Advanced Development and Cloud Infrastructure Services groups. “I like to do cool, new things,” he says. He was concerned if he stayed at SURFnet, “eduroam might still be my hobby project.” Plus, as he points out, “Truly interesting technologies get a life of their own. I’m pretty sure Vint Cerf didn’t think that 4 billion people would be on the Internet. And I am pretty sure that Tim Berners-Lee was just solving his own problem.”

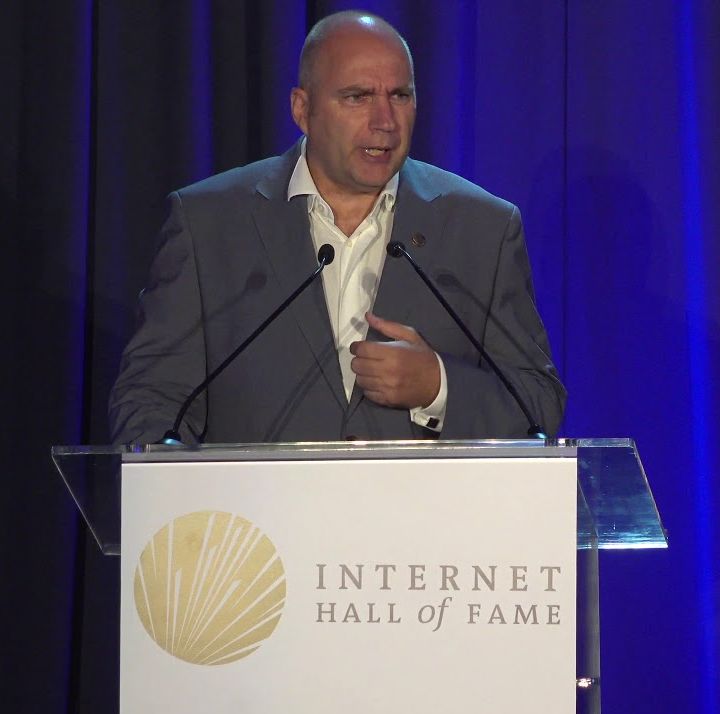

Today, the man who says “sure” is back in a role that puts him adjacent to eduroam’s ongoing expansion. Wierenga is chief information and technology officer for GÉANT.

Asked about eduroam’s influence today, Wierenga refers back to its collaborative nature. Working together, “sets the R&D world apart from the commercial world,” he notes. “eduroam paved the way for having a global, hierarchical structure where NRENs work together, and that trickles down to the individual user.”

Beyond its influence in the academic world, Wierenga thinks we’re only beginning to see how eduroam will impact the wider world of Internet users. “It’s started with initiatives like Passpoint where you can roam between wifi providers. That is very much the eduroam architecture with a few twists that make it even smarter.” The newly launched OpenRoaming, which has companies like Cisco, Google and Apple signing on, could bring eduroam-like access to the masses.

“Something I thought of twenty years ago to solve my own problem could be the default way for millions of people to access the Internet,” marvels Wierenga. In his typically understated way, he remarks, “That’s pretty cool.”

Also “cool” in his estimation is the work his current team is collaborating on. Wierenga is now the technical coordinator of the biggest European open-science cloud project. He no longer expects to be the one who comes up with breakthrough ideas. “By creating the environment, by stimulating people to do new and exciting things, sure, that’s enough reward.”